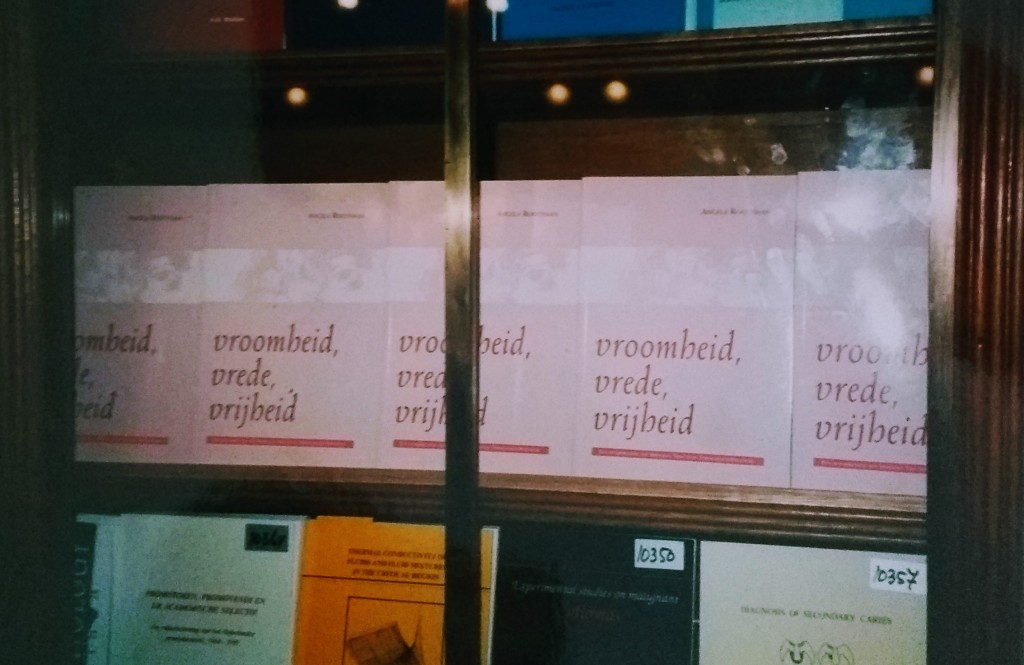

On June 14th, 1996, I saw this scene – the cortege of professors, with the university janitor in front, walking solemnly to their designed seats to interrogate me on my PhD thesis. I was lucky to be able to publish the thesis too, and the day of the promotion was the official day of its release. Following tradition of the University of Amsterdam, the city university, copies were already displayed in the reception room where we would go after the ceremony, in its solemn solid wood book cases, behind glass doors.

I was lucky in many respects. I had fulfilled my childhood desire to write and publish a book. A wide selection of old and new friends had come to support me on this day. Many family members were there. Several colleagues from my new university, the Vrije Universiteit, the ‘other Amsterdam university’, where I had acquired a postdoc position, were present. Good friends had helped to organize an afterparty at my home.

However, next to all the positives a cloud also hung over the event. A cloud reflecting the anxieties I had suffered during the eight years of struggle that was the way to the PhD. Anxieties resulting from hurdles that had almost let me quit the work several times. The competition between universities where I had sought guidance. Financial issues between them over my case, after my first supervisor had died and I had to find a successor for her. A conflict, after promising work before, with my second supervisor. My own financial issues, following bad advice and my stubbornness to not want to ask for an extension of my fellowship.

All these things maybe resulted from a lack of understanding of academic culture on my part. Nowadays people term someone like me a first generation PhD. My father had finished university studies up to the Masters level. In my mother’s family (I later learned) an architect grand uncle had acquired a professorship, but through the merit of his work and without a PhD. For me it often felt as a route through a minefield of expectations of the professors in power of those days, that I had to venture on my own. Not to mention going this road as a young woman in a country where almost no women were professors, and female students were seen as not more than accessories.

Still, somehow, through the cloud, I managed to be aware of what happened. I managed to enjoy every second of my achievement and academic survival. I even changed some rules, having asked to be able to sit during the ceremony, as I suffered problems with standing, being four months pregnant of my second child. The committee members put their questions forward, I replied to them, the cortege left again, they came back, and finally I was awarded the title of Doctor of Philosophy.

Now during the actual promotion, when my third and final supervisor spoke the official formula and thus performatively changed my academic status for the rest of my life, the final sentences impressed themselves on my mind – let me translate them from the Dutch:

“Value the acquired dignity as an honorable distinction and an important privilege, and therefore also never forget the duties that it imposes on you, over against science and society!”

Later I found that different universities have different formulas – and I have always been particularly happy that this one marked my transition to a doctor.

Why? Because it not only speaks of the rights the status entails, but also of the duties. The rights have been a blessing: I was able to stay in academia, an organisation like many others with its pros and cons, but for me the place to be. I was able to progress to postdoc and later assistant professor. It even has allowed me to supervise PhD students myself which is really a privilege!

The duties have never been out of my mind: to give back to society, by disseminating knowledge and insights acquired; but even more: to foster critical reflection – in a never ending process to check accepted ideas and outcomes of research. In an age of mistrust of science (and in my first language, Dutch, this means all systematic research: humanities, natural sciences as well as social sciences) to dedicate oneself to work in its garden – always weeding out prejudice and tending to the conditions for good research, makes for a wonderful never-ending adventure.

ough I was burying myself in the classical curriculum of my philosophy studies, she knew that I was really oriented toward the mystical. I protested the word, as ‘becoming one with the One’ did not attract me – a fan of negative dialectics and critical thinking. In the end, of course, we had more in common than we both would admit, and we entered into a fundamental conversation that lasted for 16 years. Then my friend (who had changed to religious studies in 1981, out of protest against what we now call the white canon in philosophy) at the moment she was about to start her PhD project on sufi mysticism in the middle ages, and already was making headway with learning Arabic and Persian, died.

ough I was burying myself in the classical curriculum of my philosophy studies, she knew that I was really oriented toward the mystical. I protested the word, as ‘becoming one with the One’ did not attract me – a fan of negative dialectics and critical thinking. In the end, of course, we had more in common than we both would admit, and we entered into a fundamental conversation that lasted for 16 years. Then my friend (who had changed to religious studies in 1981, out of protest against what we now call the white canon in philosophy) at the moment she was about to start her PhD project on sufi mysticism in the middle ages, and already was making headway with learning Arabic and Persian, died.