When I was researching for my master’s thesis, I focused on forgotten European 17th century thinkers, and got hooked on the old prints reading room. The only things you were allowed to take inside were paper and a pencil. The pages of those old books were made of acid free pulp, and their covers of leather, so they were much stronger than newer ones, but still the reverence asked to keep them in shape for future centuries attracted me. Forgotten or not, heretical or not, the remains of that age were still treated like temple treasures. My research reached a dead end, back then, as the prints didn’t answer all my questions. And I had no clue how to find my way in old archives, if they even existed for the material I needed, and I left the historical track in philosophy.

Recently, this past month of May, I repaired my former cluelessness when I entered an archive for the first time, determined to just find some answers about Placide Tempels (1906 -1977) and his Bantu Philosophy that the literature didn’t provide. I was inspired by the work of a cultural historian I had met, which had shown me how historical data can give us an informed view on the complex ideological and intellectual struggles in the end days of colonialism and its aftermath – this type of work should fill the gaps on the book I was researching on.

I research Bantu Philosophy not however as part of colonial history, not from an interest in missiology or religious studies, but to understand its philosophical aim and impact. Among philosophers interested in African philosophy the book is contested – a classic, yes, the source of a long debate on the nature of African philosophy, that too, but ‘real’ philosophy (in itself a suspicious classification) – doubtful. Philosophers such as Paulin Hountondji and Eboussi-Boulaga classified it as ethnophilosophy, one of the many specialized ethnosciences, a part of cultural anthropology more or less, and no constructive philosophy in itself. Ethnophilosophy or not, postcolonial thinkers such as Aimé Césaire and Frantz Fanon criticized it as just another contribution to the colonial system, as it focused on the spiritual, not on the material conditions of the colonized. The most seriously argued positive interpretation of Bantu Philosophy has been given by Valentin Mudimbe, who read the work – even if ethnophilosophical – as opening our eyes for what philosophy can be, beyond its too narrow definition in the modern age.

One of the reasons why Tempels himself was never easily taken serious as a philosopher was because he was trained a priest, not an academic philosopher, and his attempt to articulate an African ontology, the ontology of vital force, was considered by many to remain stuck in describing a worldview among others, a cultural thing, not the ultimate logical structure of reality as disciplinary philosophy was supposed to do. I had supposed, after reading all those interpretations, that Tempels maybe was not too serious about the philosophical part of his endeavour, that he had only wanted to improve missionary activity in Africa, and to change the very negative view of African humanity to that end. How wrong I was.

The unending stream of letters that rest in the archive – exchanged between him and befriended intellectuals on his ideas, as well as concerning the spread and publication of his work with more distant contacts (among them several influential phenomenologists of those days) show that Tempels was very much concerned about the philosophical implications of his work, and that contemporary philosophers were also interested in that aspect. His aim was not to present an African worldview, calling it a philosophy, as another culturally interesting object in the world of (colonial) knowledge. He was – on the contrary – convinced that European philosophy was on a dead end road, as it had forgotten a more fundamental understanding of reality as vital force, that appeared present to him in many non-European philosophical systems, among them Daoist philosophy, Native American philosophies, and Bantu philosophy.

Was he right in his view? Did he convince in his attempts to be taken seriously? Did he not overplay his hand by describing – as a foreigner – what indigenous Baluba people told him about their understanding of reality? Was his being part of the colonial system (even though he held a critical view of assimilationist ideas in missionary work) not a too heavy burden on his work all the same? Too many questions, and let me make it clear: it is not my aim to defend Bantu Philosophy or its author before the court of decolonial history. My aim is to dig through the mess that colonial history is, to see how someone followed a strong calling to articulate a new approach in philosophy, how he (mis)understood what he was doing, maybe, and how he was (mis)understood by his contemporaries. My motive: all of this is not finished, of that I am convinced. The past is not over, it is still at work, and we still have to work through it to have a future together, as humans on this earth.

Philosophy curricula rarely include non-European “great thinkers”, and even less take philosophy seriously that has never been owned by individuals with “great” names, but that often was not owned at all, but still practised as the all too human effort to understand life and our place in it, and to guide ourselves while living here, now – in all kinds of societies and ages. To create a fundamental discussion of the standard curricula and their blindness to most human reflection outside that of a few “great men”, can only be done by looking and listening in other places than the all too familiar instruction books of philosophy – in real conversations with real people, and partly also in forgotten letters in a colonial archive.

The organisor of a yearly philosophical summer week, Dr. Hälbig, had found my

The organisor of a yearly philosophical summer week, Dr. Hälbig, had found my  that suddenly appeared as a non-issue. For everything here was so German, including the appropriation of Kant, who was mentioned in every second sentence, so to speak, and always with the full realization of the very specific historical and cultural context of his philosophy. No, things were even more localized, for, as Germans do – always discussing the differences between their constituent peoples at dinner or at the bar (in this case the closest two – the Frankish and the Swabians), there was no escaping the grounded and situated nature of the philosophy being done. It kind of relieved me. After all we are all in the same boat: Anglo-saxons, French, Swabians, Tamils, Han-Chinese, and Igbos – we all come from our own fields with different animals, foods and fruits, and our own histories of power struggles over them, and the identities we developed while tending to them. And from these very local circumstances somehow in all cases thoughts emerge that may attract others from other fields and languages, making them interlocal, although never universal or global in asimple manner. In this case the fields grew grapes.

that suddenly appeared as a non-issue. For everything here was so German, including the appropriation of Kant, who was mentioned in every second sentence, so to speak, and always with the full realization of the very specific historical and cultural context of his philosophy. No, things were even more localized, for, as Germans do – always discussing the differences between their constituent peoples at dinner or at the bar (in this case the closest two – the Frankish and the Swabians), there was no escaping the grounded and situated nature of the philosophy being done. It kind of relieved me. After all we are all in the same boat: Anglo-saxons, French, Swabians, Tamils, Han-Chinese, and Igbos – we all come from our own fields with different animals, foods and fruits, and our own histories of power struggles over them, and the identities we developed while tending to them. And from these very local circumstances somehow in all cases thoughts emerge that may attract others from other fields and languages, making them interlocal, although never universal or global in asimple manner. In this case the fields grew grapes.

Beyond the self-aggrandizement of philosophies that claimed to end history, to make a radical new start, introduce a new ‘school’, or to even destruct philosophy itself. This new, fresh, orientation I witnessed, had nothing of that – instead it boasted all things modest: doing serious historical work, analyzing the intertwinements of religion, politics, and culture patiently and honestly, and above all: working on translation in the broadest sense – making little known texts and views a bit more well known, introducing ‘marginal’ thinkers and their work to a wider audience – and in all that: shifting the

Beyond the self-aggrandizement of philosophies that claimed to end history, to make a radical new start, introduce a new ‘school’, or to even destruct philosophy itself. This new, fresh, orientation I witnessed, had nothing of that – instead it boasted all things modest: doing serious historical work, analyzing the intertwinements of religion, politics, and culture patiently and honestly, and above all: working on translation in the broadest sense – making little known texts and views a bit more well known, introducing ‘marginal’ thinkers and their work to a wider audience – and in all that: shifting the  We were in the ‘francophone’ sphere of the African continent: in a sphere and in a place – opening a space for thought. But English was a conference language too, and mostly well understood. Wolof often served to accomodate the organizational processes of course. And I was lucky to also be able to retreat for a while in my own language, Dutch, with colleagues from NL I only truly got to know in Dakar, as such things go. So, the issue of translation was never far away – especially because the man who was the centre of it all, fondly called Bachir by his friends, embodies the issues of translation in his

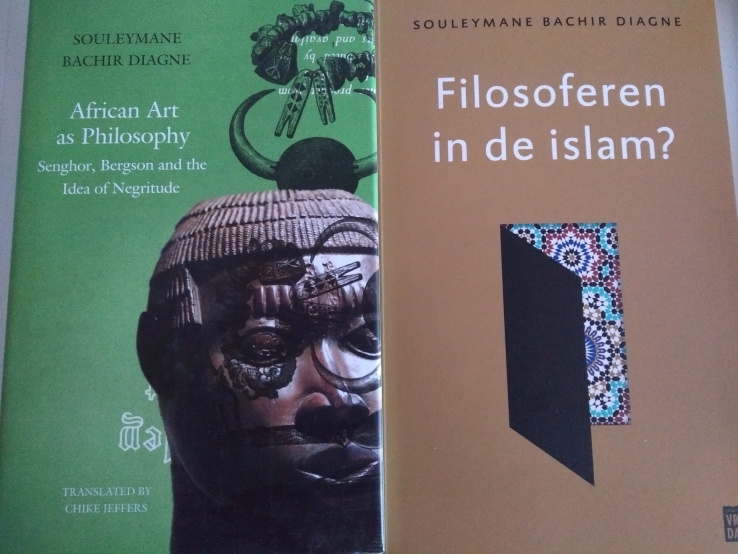

We were in the ‘francophone’ sphere of the African continent: in a sphere and in a place – opening a space for thought. But English was a conference language too, and mostly well understood. Wolof often served to accomodate the organizational processes of course. And I was lucky to also be able to retreat for a while in my own language, Dutch, with colleagues from NL I only truly got to know in Dakar, as such things go. So, the issue of translation was never far away – especially because the man who was the centre of it all, fondly called Bachir by his friends, embodies the issues of translation in his  Involved in such negotiation Souleymane Bachir Diagne critically investigates thinkers such as Senghor and Bergson, Iqbal and Thierno Bokar, – meanwhile fearlessly researching how religion and modernization, democratic movements, searches for identity as well as equality, interact, mix, and may be used as ways to open up towards ourselves and each other.

Involved in such negotiation Souleymane Bachir Diagne critically investigates thinkers such as Senghor and Bergson, Iqbal and Thierno Bokar, – meanwhile fearlessly researching how religion and modernization, democratic movements, searches for identity as well as equality, interact, mix, and may be used as ways to open up towards ourselves and each other. tise in teaching how to teach philosophy, were welcomed to spend some days for exchange with our Colchester colleagues in what our host, Matt Burch, had named a ‘pedagogy workshop’. A very apt title, as we gathered in different formats around pedagogy -explicitly on our common field: philosophy. We were kindly invited to observe teaching approaches in the newly formed summer program for bachelors students, to participate in a research activity on ‘race and gender’ theory, and to present our own views on philosophy pedagogy amidst an engaged group of Essex-colleagues.

tise in teaching how to teach philosophy, were welcomed to spend some days for exchange with our Colchester colleagues in what our host, Matt Burch, had named a ‘pedagogy workshop’. A very apt title, as we gathered in different formats around pedagogy -explicitly on our common field: philosophy. We were kindly invited to observe teaching approaches in the newly formed summer program for bachelors students, to participate in a research activity on ‘race and gender’ theory, and to present our own views on philosophy pedagogy amidst an engaged group of Essex-colleagues. so concerning societal, personal and cultural matters. That was twenty years ago. And over the years, developing several dialogical approaches as a service teacher myself (as well as in the philosophy bachelor and master programs), I introduced more and more content into the courses from other places than the obvious European and American ones – teaching, for instance, on the links between diverse African philosophies of communality and individuality and American theories of the social self, or on Foucault’s work on the prison in comparison with that of Angela Davis, using Rwanda’s gacaca courts as an example of new experiments of doing justice in cases of violence on an extreme scale. I was finding my way experimentally, as I didn’t want to close myself in in new – alternative – schools that were already emerging here and there. I showed, in my presentation, how I always make a point of including photos of the philosophers from different continents on my powerpoints, to create an – also visually – inclusive space for the students to learn together.

so concerning societal, personal and cultural matters. That was twenty years ago. And over the years, developing several dialogical approaches as a service teacher myself (as well as in the philosophy bachelor and master programs), I introduced more and more content into the courses from other places than the obvious European and American ones – teaching, for instance, on the links between diverse African philosophies of communality and individuality and American theories of the social self, or on Foucault’s work on the prison in comparison with that of Angela Davis, using Rwanda’s gacaca courts as an example of new experiments of doing justice in cases of violence on an extreme scale. I was finding my way experimentally, as I didn’t want to close myself in in new – alternative – schools that were already emerging here and there. I showed, in my presentation, how I always make a point of including photos of the philosophers from different continents on my powerpoints, to create an – also visually – inclusive space for the students to learn together.